|

It is easy to be skeptical of the hype surrounding the next “green” energy technology that is going to lift us into a blissful future of sustainability. But, dig down a layer and you see this is a classic story of “letting the perfect be the enemy of the good.” All energy-related technologies have impacts. So, if some purported green technology to you means “no impact” or even “net positive impact,” then I have news for you – you are in the business of pipe dreams. Even if we can agree on a technology being an unalloyed good, like energy storage or electric vehicles for instance, then our critical eye turns to the materials that go into making that newfangled technology. After all, those materials were undoubtedly mined, extracted, processed, and distributed in ways that are deleterious to the environment, right? This is where we need to put on our thinking caps, and unpack the easily made criticisms that all technologies (and the materials of which they are made) have net negative environmental impacts. The key here is the “net” concept, as in weighing the good with the bad. Seen through this lens, we can start determining what technologies generate a net environmental good for society, and which do not. But this is no simple task, as we will see… A perfect case study to illustrate this challenge concerns lithium, which is one of the key elements in battery technology. If there is one thing that most energy experts will agree upon, it is the absolute necessity of more energy storage technology to modernize the electric grid to allow for greater flexibility, security, and more variable renewable energy generation. Battery technology is also enabling a revolution in the transportation industry with the entry of increasingly affordable (and admittedly cool) electric vehicles. With these two trends, you have the perfect confluence of demand-side factors that have exponentially increased the demand for lithium. And the backlash has been entirely predictable. Here I explore 5 storylines that define the contours of whether lithium is a green story, or just greenwash. 1. Mining deservedly has a bad rap, but it is a necessary cost of modern civilization Let’s be clear – mining is a nasty business. The environmental and human health impacts of mining operations for many of society’s most essential resources are significant. There is no denying that even with the most stringent laws and mitigation efforts never fully account for the damage that is inflicted by mining. However, accepting that mining has some degree of impact is something that we all implicitly have accepted as a necessary cost of modern civilization. For those environmentalists (which I call myself) or impact investors (who are my clients, colleagues, and collaborators) whose hackles have gone up – let me ask you one question. What technologies have you forgone for the sole purpose of reducing the demand for the resources that are mined from the earth? Electronics, planes, cars, phones, computers, batteries, air conditioning, and the list could go on. I would venture a guess that even the greenest environmentalist or the most socially conscious investor has not forsaken all the technological comforts of modern life. That is not to say that we should ignore the impact of mining, especially since those impacts are unevenly distributed, and are often disproportionately affecting regions and populations that are less advantaged economically and politically. Regulating the impact of mining activities is an absolute imperative, and we could do a much better job in many accounts. Moreover, there are certain resources which we should unequivocally seek to progressively eliminate from our diets. Yes, I am talking about fossil fuels, but that is another debate for another time. On the other hand, there are those “keystone” resources that are needed in increasingly greater quantities to support the transition to a low-carbon economy. Lithium is one such keystone resource, and the challenge is to weigh the benefits of lithium-ion battery technology with the cost of mining lithium. 2. Not all mining is creating equal -- lithium vs. the bad boys It is probably not much comfort to claim that lithium mining is not nearly as impactful as mountaintop removal for coal or extracting tar sands in Alberta. These are two of the bad boy extremes of mining, and their impact is irrefutably devastating. Lithium mining, in comparison, is relatively benign. Most lithium mines would not appear to the untrained eye to be mines at all. That is because most lithium is extracted from salt brines through evaporating salt ponds. Brine deposits represent approximately 66% of global lithium resources, and the majority of lithium mining is done through brine mining as opposed to more conventional hard rock mining. The reason is that salt brine lithium mining operations are smaller-scale, cheaper, less risky, and cleaner than lithium rock mining. The process is quite simple. Subterraneous brine from unconsolidated sediments (gravel, sand, silt, etc.) is pumped and concentrated in evaporation pools on the surface. The linked pools that you see in the image below have progressively higher concentrations of lithium. After 9-12 months of evaporation, the concentrate reaches one to two percent lithium, which is then further processed into end products such as lithium carbonate, lithium hydroxide, or other forms. Sounds like a pretty clean operation, right? Well, this is mining, after all. And mining comes with impacts, even if the impact of lithium brine mining is on an entirely different scale than many other resources. Mining companies prospecting for lithium require extensive extraction operations and water in a what are generally very arid lands. The land required for the typical lithium brine mining operation is substantial, though not as extensive as many mining operations. The Clayton Valley mine in Nevada, for instance, is 9,500 acres, which should produce 816,000 tons of lithium over the course of its life. The evaporation ponds require large quantities of water, which can compete with local drinking and irrigation water. Lithium mining regulation is a national issue, and some nations have better governance, permitting, and enforcement infrastructure than others. Most countries involved in lithium mining are relatively well-equipped to manage environmental and human health impacts. However, it is not uncommon for there to be disputes over mining rights, operations, and the mitigation of impacts on the local environment and communities. An investor interested in this space would be well-served by factoring in the role of community support and the ability of the mining company to address environmental concerns in their operations. 3. Can the small world of lithium mining meet the growing demand for lithium? Though lithium is a not a rare element, it is highly diffuse, with only a small number of regions worldwide with concentrations high enough to be mineable. 97% of lithium production came from just four countries. Australia is the top producer worldwide with 14,300 tons of production in 2016 followed by Chile (12,000 tons), Argentina (5,700 tons), and China (2,000 tons). The lithium market is similarly controlled by a remarkably smaller number of companies. Chinese producers (Tianqi and others) control 40% of the market. SQM (26%), Albemarle (20%), and FMC Corp (12%) – control the majority of the rest of the market, while the small companies have been pushed into the margins with just 2% of global market share. You Tesla investors (or Elon Musk groupies) might be asking – where is the Gigafactory going to get their lithium? They were smart of think about the lithium supply chain as they selected the Gigafactory location, which is conveniently located close to Silver Peak mine in Nevada, which until recently was one of the only lithium mines in the US. That is not likely going to meet their needs at full production capacity, but it is a start. The rapid growth in demand for lithium has sparked a veritable gold rush in emerging lithium markets like Nevada. This begs the question – how much lithium do we have? And can the supply of lithium possibly keep up with demand? The proven economically recoverable reserves of lithium are on the order of 14 million tons. At current levels of production, that would afford us 400 years of lithium. To put this in perspective, many other mined metals have less than 100 years of proven reserves assuming current levels of demand. If you count known resources of lithium, which amount of nearly 40 million tons, then we have more than a millennium of lithium on our hands at current consumption levels. If lithium production increases at 10% per year in perpetuity, that would give us just 40 years. But, if we extrapolate these recent annual growth production rates for 40 years, then production would have grown to 40x what it is today. Clearly, here we enter the world of fantasy, or as mathematicians like to remind us – our brains are terrible at interpreting exponential trends. So, call the most likely lithium supply-demand scenario somewhere in between 40 and 400 years. And that is only if we assume that none of the known resources become economically viable to mine and that demand for virgin lithium supply will not be curtailed in the future due to lithium recycling. Which brings me to the point… 4. Remember the last of the three Rs - Recycle The “3 Rs” – Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle – were probably burned into your memory in middle school. In the case of lithium, the last R is a big deal, and one that is often overlooked. It turns out that lithium-ion batteries are well-suited for recycling. An expert from Panasonic recently claimed that he expects to see recycling rates for lithium batteries to approach 100% in the future. That might be a little bullish, but I like the ambition. Until recently, recycling the lithium-ion batteries did not make economic sense. Lithium only makes up about 3% of the production cost of a battery, and the other metals typically found in lithium-ion batteries (e.g., cobalt, nickel, copper) are much more valuable. So, recycling a battery just for the sake of reusing the lithium does not make sense. A more comprehensive recycling of all the valuable battery components, however, does make sense. If only it were that simple! Suffice it to say that there is legitimate debate about how to recycle lithium-ion batteries economically and at a meaningful scale. There has been a large amount of government and private sector investment in research and development of lithium-ion battery recycling techniques. These investments are spurred by the recognition that (1) recycling needs to solved so that lithium-ion batteries can scale even if supply constraints reached in the future and (2) there is a tremendous economic opportunity here given the dynamics of demand for lithium. Speaking of which… Source: The Economist 5. Technological progress may reduce impacts of lithium brine mining even further

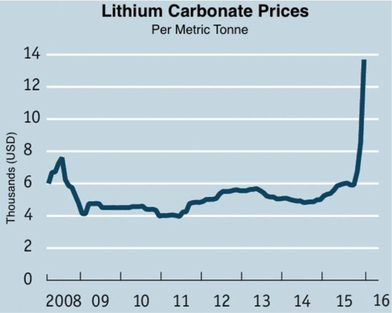

According to a Credit Suisse report, "Lithium brine deposits typically outperform hard rock lithium sources on cost, sustainability and permitting. This gap is becoming more pronounced when we take into account technological advancements in brine processing…” Technological progress has already made lithium brine mining much more economical than lithium rock mining (which takes place primarily in Australia and China), and the majority of new mines employ this cheaper, safer, and more efficient technique. But progress has not stopped there. A new process is being developed by an Italian company called Tenova SpA. This method really takes the mine out of the mining, in some sense. The process uses an ion-exchange system to strip the lithium and then returns the water to the ground. This would eliminate the need for evaporation ponds, which is one of the only elements of the mining process that pose a risk to human health. Importantly, it would also reduce production time to hours rather than months, while also yielding a higher concentration of lithium. The only catch is that the process has not been proven at scale, though there are some pilot projects functioning to work out the kinks. Some of the big players in the lithium brine mining market, such as Albemarle, are skeptical about the technology and have concerns about returning the water to aquifers under high pressure. They may be looking over their shoulders at the natural gas fracking industry, whose practices have called into question the wisdom of such high pressure pumping in underground geological structures. Only time will tell if this or another technology enters the market that would even further reduce the environmental impact of lithium brine mining. Regardless, the price signals in the lithium market support this type of innovation looking to the future. In Conclusion The lithium market is undergoing a rapid expansion due the rising demand for lithium-ion battery technology, in addition to its more established uses in chemicals, ceramics, and manufacturing. This has forced us to scrutinize just what unintended or hidden impacts may be associated with lithium mining, especially as it scales to historically unprecedented levels of production. Not only is lithium brine mining, the most common form of lithium mining, one of the most benign forms of mining, but it continues to reduce its environmental impact through technological advances. There are still local environmental and human health concerns to be addressed in any mining operation, but there are effective regulatory structures in place to manage such risks. Nevertheless, a higher degree of vigilance on the part of investors and mining companies in monitoring environmental and human health impacts is warranted. Resource scarcity is also a virtual non-issue, as proven reserves and known resources can legitimately support lithium production for literally centuries. And that does not even account for the eventuality of recycling lithium-ion batteries. Now place these impacts within the context of lithium being an essential element in the battery technology that we need to support the transition to a low-carbon energy system and the deployment of electric vehicles. The case to support the environmental merit of lithium mining should be self-evident. Comments are closed.

|

Details

sign up for ironoak's NewsletterSent about twice per month, these 3-minute digests include bullets on:

Renewable energy | Cleantech & mobility | Finance & entrepreneurship | Attempts at humor (what?) author

Photo by Patrick Fore on Unsplash

|