|

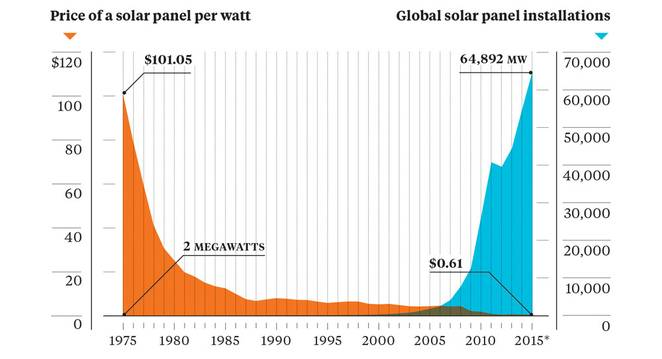

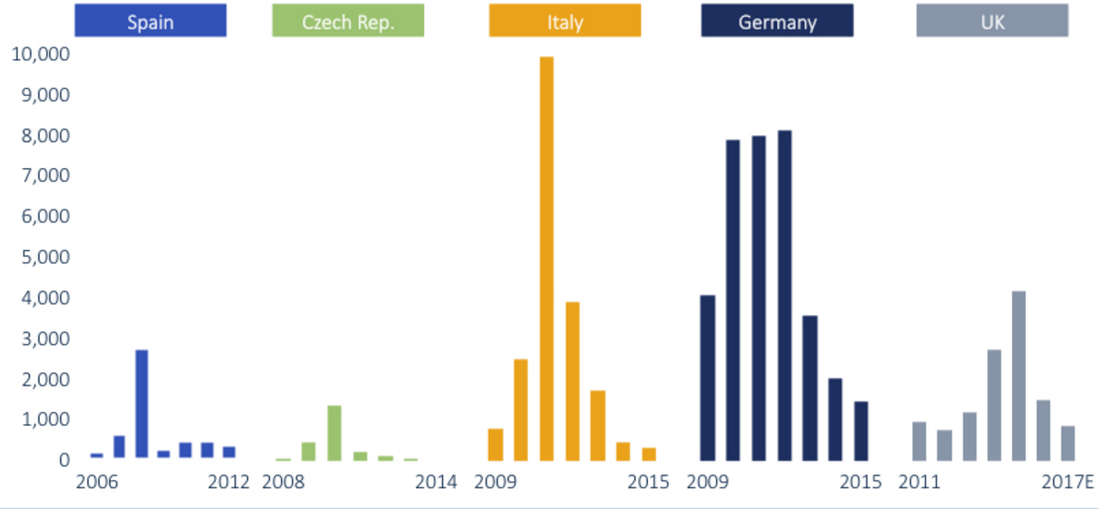

Feed In Tariff (FIT) programs have been the lynchpin of solar growth, but is it time to move on? Source: Earth Policy Institute/Bloomberg Feed-in tariff (FIT) programs were designed to entice new entrants into the solar market during a time of learning and experimentation. Initially, they were designed as value-based instruments in which compensation was tied to various external benefits, such as avoided externalities (fancy term for coal plant pollution). But this model was a bit pie-in-the-sky, and left a lot of uncertainty and unpredictability on the table for investors and developers to navigate. The resulting high project financing costs ended up being a major deterrent to the type of catalytic growth that was hoped for. The real magic of the feed-in-tariff was unlocked when there was a shift to cost-based instruments, wherein a solar developer would get compensated for the costs of development plus some reasonable rate of return. The fixed-rate, long-term guarantee of cash flows was music to investors’ ears, and the solar market was off to the races all across the EU, China, India, and South Africa. Interestingly, no North American country has instituted a FIT program to date, and rather have opted for more circuitous policies such as Renewable Portfolio Standards. We now have a solid track record by which to evaluate the successes (and failures) of FIT programs around the world. On the surface, much of the success of solar markets worldwide is attributed to FIT programs. But there is a creeping concern that this success will not last much longer. FIT programs solved one problem by creating stable, long-term cash flows for solar projects, which could be underwritten and financed by savvy investors. This accelerated adoption and experimentation with different technologies and business models, but more importantly it sped up learning (decreases in costs due to experience or scale). In solving this market catalyst problem in the short term, governments left the door open in the long-term for gaming the system if and when solar prices (really LCOE) started to dip well under the FIT rates. And that is precisely what has started to happen. The bull rush to obtain legacy FIT program rates once technology costs plummeted has fueled a massive boom in solar. On the the surface, this seems like a great problem to have. More solar! But, this is a case of too much too soon, and governments are responding by pulling back on their FIT programs and leaving a wake of solar developers scrambling to make their projects pencil. Source: GTM Research The European renewable miracle has been taking some nasty hits lately. Even the energy transition darling, Germany, has not been immune to the pervasive bust cycle that is spreading across the continent. What changed so quickly, you may ask? Well, it is the classic story of a good thing gone bad. The FIT programs that accelerated solar adoption so quickly in years past are now becoming the victim of their own success. Where they erred was in making the terms so enticing for so long that they ended up overheating the solar market. There is a delicate balance between creating an incentive to attract risk-taking early adopters and reducing or retracting the incentive once the economics of the market support broad participation. Or, in other words, they just let too many players at the table, and this time, the cards were stacked against the house. Governments underestimated the speed at which solar prices would fall, which left them in the undesirable position of having already committed to paying well above market prices. It was boom times for the solar industry, but it could not last. The graphs above look like tulip mania (if this reference eludes you, please read for some amazing dinner table chatter) for crying out loud. Germany had three years of putting over 8 GW online. Italy spiked in 2011 with nearly 10 GW of solar, only to plummet to under half of that in the following year. The UK has witnessed a remarkable growth in solar, only to cut the FIT program by 65% in one fell swoop. Similar patterns were seen in many other EU countries. And let’s not forget Japan, whose boom-bust cycle dwarfs those of all of the ill-fated EU countries already mentioned. Japan is still in the top 3 globally in terms of annual solar capacity installed, but is headed for a protracted decline in solar over the years to come, again due to an over-aggressive FIT program. But FIT programs are so simple and elegant. What alternatives exist, you may ask? Source: GTM Research Letting go of a good thing is hard, especially for an industry like solar that may suffer from a tinge of PTSD from the head-spinning boom-bust cycles of the past decades.

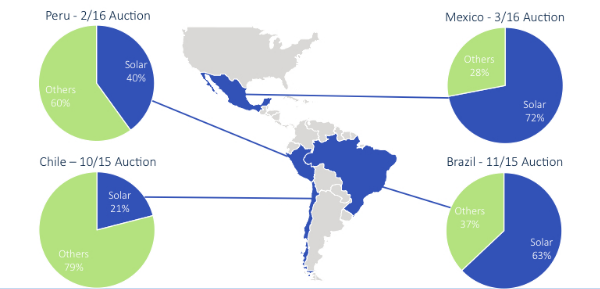

After all, with the FIT structure solar did not necessarily have to directly compete with other generation technologies. A decade ago, that was just fine because solar would not have been competitive. Solar needed an incubation period to slide down the learning curve to lower, more competitive prices and meaningful deployment scale. Now that solar can tout itself as being one of the most cost effective electric generation technologies out there, there needs to be an increasing willingness to actually compete in markets with other generation technologies. Latin America has started to buck the FIT model in favor of an auction process in which solar competes with other generation technologies, both from independent power producers and incumbent utilities. This has helped feed a boom in Latin American solar, as it turns out that solar can beat out nearly all other generation technologies on a pure LCOE basis. Nearly three quarters of new capacity additions in Mexico will come from solar, easily more than 1 GW. Brazil is in the same league. And various EU countries and India are also doubling down on auctions. But, auctions are not a panacea. We have all seen auctions in the movies, and the meme of the irrationally exuberant bidder going well beyond their true willingness (or ability) to pay in order to secure the prize. While we all hope that power producers are somewhat more measured and rational in their approach to bidding in these markets, there remains the possibility that competing in auctions may drive prices down quickly to unsustainable (even unprofitable) levels. In fact, some early evidence in the auction tea leaves is that even these markets can overheat as bidders aggressively pursue market share. On the one hand, it may be good for business in the short-run, and auctions may effectively accelerate learning and cost reductions. But, on the other hand, auctions run wild may undermine the long-term viability of the ecosystem of power producers feverishly competing to keep up with the Joneses to survive. Exuberant bidding to support short-term growth is not a phenomenon that should feel altogether unfamiliar, as it is precisely what drove SunEdison to bankruptcy. Further reading: As Feed-In Tariffs Wane, Auctions Are Enabling the Next Wave of Solar Cost ImprovementsFeed-in Tariff: A policy tool for encouraging the deployment of renewable energy technologiesInnovative Feed-in Tariff Policy Designs that Limit Policy Costs A Policymaker’s Guide to Feed-in Tariff Policy DesignFeed-in Tariff Policy: Design, Implementation, and RPS Policy Interactions Comments are closed.

|

Details

sign up for ironoak's NewsletterSent about twice per month, these 3-minute digests include bullets on:

Renewable energy | Cleantech & mobility | Finance & entrepreneurship | Attempts at humor (what?) author

Photo by Patrick Fore on Unsplash

|